Streaming live on the Co-Creator Radio Network on Tuesday, September 20, at 11 a.m. Pacific time/2 p.m. Eastern time, on her show "Why Shamanism Now?: A Practical Path to Authenticity," Christina Pratt talks to Richard Whiteley, author of The Corporate Shaman, who answers the question so very many are asking these days: What is happening around us? We see severe weather, colossal oil spills, and species dying off. We see corruption in banking, politics, and religions around the world. We see riots, anger, and hopelessness in our communities. According to Whiteley, this is "shamanic dismemberment": the experience of being pulled apart, eaten, or stripped layer by layer, down to the bare bones on a global scale, allowing for a shift of awareness and transformation of collective consciousness. And perhaps more importantly, Whiteley shares why he feels there is reason to be hopeful and how we can participate with spirit in the Remembering so that the world we co-create is different than before. Prior episodes from "Why Shamanism Now" can be downloaded for free from the iTunes library.

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Saturday, September 10, 2011

The Symbolization Process of the Shamanic Drum

In her scholarly article "The Symbolization Process of the Shamanic Drums Used by the Manchus and Other Peoples in North Asia ," Lisha Li establishes a universal framework describing how the drum as a symbol transmits symbolic meanings among shamans, people and the spirit world. She provides an in-depth analysis of the symbolic functions of the drum from an ethnomusicological point of view. All elements of drum music such as timbre, rhythm, volume and tempo play an important role in Manchu shamanic ritual. By using different parts of the drumstick to play on different parts of the drum, different timbres can be produced for transmitting different meanings. Different rhythms transmit different meanings and enable the shaman to contact different beings in different realms of the cosmos. Volume and tempo arouse feelings in the listener and communicate symbolic meanings directly as aural sense experience. The drum is also a visual symbol loaded with symbolic meanings.

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Coast Salish Shamanic Spindle Whorls

The spindle whorl, once an indispensable tool for aboriginal weaving, is no longer just a museum artifact, but a symbol that has been reborn as an icon to globally identify the cultural lineage of the Coast Salish people from the Pacific Northwest Coast  , and visit Coast Salish artist

, and visit Coast Salish artist Susan Point's website.

Saturday, September 3, 2011

Shamanic Music: Sounds of the Soul

© 2011 by Michael Drake

Shamanic music is traditionally performed as part of a shamanic ritual, however it is not a musical performance in the normal sense. The shaman is focused on the healing intention or spiritual energy of what he or she is playing, to the point that musical considerations are minimal. Shamanic music is improvised by the shaman to modify movement and change while actively journeying into the spirit world. It is a musical expression of the soul, supporting the shamanic flight of the soul. Sacred music is directed more to the spirit world than to an audience. The shaman's attention is directed inwards towards communication with the spirits, rather than outwards to any listeners who might be present.

A shaman uses various ways of making sounds to communicate with the spirits, as well as relate the tone and content of the inner trance experience in real time. Shamans may chant, clap their hands, imitate the sounds of birds and animals, or play various instruments. Of particular importance are the shaman's drum and song. Each shaman has his or her own song. It announces the shaman to the spirits and proclaims, "this is me…please help me." The song is usually sung near the beginning of the ritual and is often accompanied by drumming.

The sound of the shaman’s drum is very important. A shamanic ritual often begins with heating the drum head over a fire to bring it up to the desired pitch. It is the subtle variations in timbre and ever-changing overtones of the drum that allow the shaman to communicate with the spiritual realm. The shaman uses the drum to open portals to the spirit world and summon helping spirits. As Tuvan musicologist Valentina Suzukei explains, "There is a bridge on these sound waves so you can go from one world to another. In the sound world, a tunnel opens through which we can pass -- or the shaman’s spirits come to us. When you stop playing the drum, the bridge disappears."1

When a spirit is invoked, there is often an accompanying rhythm that evolves. Shamans frequently use specific rhythms to "call" their spirit helpers for the work at hand. A shaman may have a repertoire of established rhythms or improvise a new rhythm, uniquely indicated for the situation. Shamans may strike certain parts of the drum to access particular helping spirits. The drumming is not restricted to a regular tempo, but may pause, speed up or slow down with irregular accents.

Shamans are also known for their ability to create unusual auditory phenomena. According to Scottish percussionist Ken Hyder, who has studied with Siberian shamans, "Shamans tend to move around a lot when they are playing, so a listener will hear a lot of changes in the sound…including a mini-Doppler effect. And if the shaman is singing at the same time, the voice will also change as its vibration plays on the drumhead."2 Furthermore, in a recent ethnographic study of Chukchi shamans, it was found that in a confined space, shamans are capable of directing the sound of their voice and drum to different parts of the room. The sounds appear to shift around the room, seemingly on their own. Shamans accomplish this through the use of standing waves, an acoustic phenomenon produced by the interference between sound waves as they reflect between walls. Sound waves either combine or cancel, causing certain resonant frequencies to either intensify or completely disappear. Sound becomes distorted and seems to expand and move about the room, as the shaman performs. Moreover, sound can appear to emanate from both outside and inside the body of the listener, a sensation which anthropologists claimed, "could be distinctly uncomfortable and unnerving."3

The Shaman's Horse

The drum -- sometimes called the shaman's horse -- provides the shaman a relatively easy means of controlled transcendence. Researchers have found that if a drum beat frequency of around 180 beats per minute is sustained for at least fifteen minutes, it will induce significant trance states in most people, even on their first attempt. During shamanic flight, the sound of the drum serves as a guidance system, indicating where the shaman is at any moment or where they might need to go. "The drumbeat also serves as an anchor, or lifeline, that the shaman follows to return to his or her body and/or exit the trance state when the trance work is complete."4

Recent studies have demonstrated that shamanic drumming produces deeper self-awareness by inducing synchronous brain activity. The physical transmission of rhythmic energy to the brain synchronizes the two cerebral hemispheres, integrating conscious and unconscious awareness. The ability to access unconscious information through symbols and imagery facilitates psychological integration and a reintegration of self. Drumming also synchronizes the frontal and lower areas of the brain, integrating nonverbal information from lower brain structures into the frontal cortex, producing "feelings of insight, understanding, integration, certainty, conviction, and truth, which surpass ordinary understandings and tend to persist long after the experience, often providing foundational insights for religious and cultural traditions."5

It requires abstract thinking and the interconnection between symbols, concepts, and emotions to process unconscious information. The human adaptation to translate an inner trance experience into meaningful narrative is uniquely exploited by singing, vocalizing, and drumming. Shamanic music targets memory, perception, and the complex emotions associated with symbols and concepts: the principal functions humans rely on to formulate belief. Because of this exploit, the result of the synchronous brain activity in humans is the spontaneous generation of meaningful information which is imprinted into memory.

Shamanic experience can be expressed in many ways: through writing, art, and film, however it must be created after the fact. The one artistic medium which can be used to immediately express shamanic trance without disrupting the quality of the shamanic experience is music. The shaman's use of sound and rhythm is an audible reflection of their inner environment. This is the traditional method for integrating shamanic experience into both physical space and the cultural group. To learn more, look inside Shamanic Drumming: Calling the Spirits.

Discography

Shamanic and Narrative Songs from the Siberian Arctic, Sibérie 1, Musique du Monde, BUDA 92564-2

Kim Suk Chul / Kim Seok Chul Ensemble: Shamanistic Ceremonies of the Eastern Seaboard , JVC, VICG-5261 (1993)

, JVC, VICG-5261 (1993)

Tuva, Among the Spirits , Smithsonian Folkways SFW 40452 (1999 )

, Smithsonian Folkways SFW 40452 (1999 )

Gendos Chamzyrzn, Kamlaniye , Long Arms (Russia) CDLA 04070 (2004)

, Long Arms (Russia) CDLA 04070 (2004)

Shamanic Journey Drumming, Michael Drake, (2008)

Power Animal Drumming, Michael Drake, (2010)

Shamanic Journey Drumming, Michael Drake, (2008)

Power Animal Drumming, Michael Drake, (2010)

Notes

1. Kira Van Deusen, “Shamanism and Music in Tuva and Khakassia,” Shaman’s Drum, No. 47, Winter 1997, p. 24.

2. Ken Hyder, ‘’Shamanism and Music in Siberia : Drum and Space,” 2008, p.2.

3. Aaron Watson, 2001, “The Sounds of Transformation: Acoustics, Monuments and Ritual in the British Neolithic,” In N. Price (ed.) The Archaeology of Shamanism. London: Routledge. 178-192.

4. Christina Pratt, An Encyclopedia of Shamanism (The Rosen Publishing Group, 2007), p. 151.

5. Michael Winkelman, Shamanism: The Neural Ecology of Consciousness and Healing. Westport, Conn: Bergin & Garvey; 2000.

Affiliate disclosure: I get commissions for purchases made through links in this post.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Shamanism and Google Consciousness

Multimedia shaman Rome Viharo is a musician, filmmaker, and founder of Media Social. In a recent TED (Technology Entertainment and Design) Talk titled "Google Consciousness," Viharo made the correlation between Peruvian shamanism and Google search -- two contradictory models of consciousness that share a share a metaphor in common -- collective problem solving. In the talk, Viharo draws a parallel between how Peruvian shamans access plant consciousness and how memes or ideas spread from person to person within a culture. Viharo says, "It essentially refers to an idea that spreads virally called Google Consciousness that plays with the idea that the Internet could become sentient, meaning conscious -- aware. The Google algorithm, especially the way we use it, is now actually a contender for being conscious. We use it as a metaphor for a collective intelligence or a collective consciousness with the participation between technology and people using the Web. What is more bizarre to consider: intelligent plants or intelligent computers?" View the TED Talk video "Google Consciousness," based in part on Daniel Dennett's model of consciousness in his landmark book Consciousness Explained .

.

Sunday, August 21, 2011

"Shamanic Journeys Through Daghestan"

In his book, Shamanic Journeys Through Daghestan , gifted storyteller Michael Berman brings to life the shamanic traditions and folk tales of the tribal clans of Daghestan, an isolated mountainous region of Russia to the North of the Caucasus Mountains along the west shore of the Caspian Sea. These 32 distinct ethnic groups, each with its own language, culture, customs, and arts, are now connected through Islam, but their ancient stories and oral traditions reveal their shamanic roots. Quests, journeys, spirit helpers and shape-shifting are common motifs within what Bergman terms "shamanic stories." Bergman argues for the introduction of a distinct genre in academia - shamanic story - that has either been based on or inspired by a shamanic journey, or one that contains a number of the elements typical of such a journey. Shamanic stories bring people directly into immediate encounters with spiritual forces, integrating healing at physical and spiritual levels. This process allows them to connect with the power of the universe, to externalize their own knowledge, and to internalize their answers. Furthermore, through the use of narrative, shamans are able to provide their clients with a language, by means of which unexpressed, and otherwise inexpressible, trance states can be expressed.

, gifted storyteller Michael Berman brings to life the shamanic traditions and folk tales of the tribal clans of Daghestan, an isolated mountainous region of Russia to the North of the Caucasus Mountains along the west shore of the Caspian Sea. These 32 distinct ethnic groups, each with its own language, culture, customs, and arts, are now connected through Islam, but their ancient stories and oral traditions reveal their shamanic roots. Quests, journeys, spirit helpers and shape-shifting are common motifs within what Bergman terms "shamanic stories." Bergman argues for the introduction of a distinct genre in academia - shamanic story - that has either been based on or inspired by a shamanic journey, or one that contains a number of the elements typical of such a journey. Shamanic stories bring people directly into immediate encounters with spiritual forces, integrating healing at physical and spiritual levels. This process allows them to connect with the power of the universe, to externalize their own knowledge, and to internalize their answers. Furthermore, through the use of narrative, shamans are able to provide their clients with a language, by means of which unexpressed, and otherwise inexpressible, trance states can be expressed.

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Awakening into Dreamtime

In her essay "Awakening into Dreamtime: The Shaman's Journey," Wynne Hanner explores the Australian Aboriginal concept of Dreamtime as a source of and guide to transforming our own world view. According to Aboriginal mythology, Dreamtime is a sacred era in which ancestral Spirit Beings formed The Creation. Indigenous Australians believe the world is real only because it has been dreamed into being. Hanner explains, "The Aborigines embrace the concept of 'reality dreaming', with reality and Dreamtime intertwined. Reality can be illusion, deception, learning, perception, experience, and is the evolution of consciousness in the alchemy of time. Reality shifts and changes like the flow of the collective unconscious, and is in constant motion creating new spiral patterns of experience. Reality, in its illusion, is the dream from which we all awaken. To understand and work with these concepts is to awaken into the dream." Read Awakening into Dreamtime and support your Dreamtime explorations with Didgeridoo for the Shamanic Journey.

Monday, August 8, 2011

"Places of Peace and Power"

Martin Gray is an intrepid National Geographic photographer whose work I have been following since meeting him in 1993 at the Earth and Spirit Conference in Portland , Oregon  , which bears beautiful testimony to his life's mission and to his deep connection to Spirit. Hundreds of full color plates capture the essence of these great pilgrimage shrines. Prior to taking each picture Martin offered up a prayer to the Spirit of the place asking them to, "fill my photographs with such feeling and power that people may one day look upon them and be magically transported to these places." It is more than evident that those prayers were answered. Martin says, "I personally consider these photographs to be telescopes through which you may peer across time and space into enchanted domains of sublime beauty."

, which bears beautiful testimony to his life's mission and to his deep connection to Spirit. Hundreds of full color plates capture the essence of these great pilgrimage shrines. Prior to taking each picture Martin offered up a prayer to the Spirit of the place asking them to, "fill my photographs with such feeling and power that people may one day look upon them and be magically transported to these places." It is more than evident that those prayers were answered. Martin says, "I personally consider these photographs to be telescopes through which you may peer across time and space into enchanted domains of sublime beauty."

Sunday, July 31, 2011

Journey into the Cave of Consciousness

Caves are akin to the classic inward journey of the shaman, which transforms the individual as well as the culture. In his 2010 documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Werner Herzog gains exclusive access to film inside the nearly inaccessible Chauvet Cave Southern France , capturing the oldest known pictorial creations of humankind. It's an unforgettable cinematic experience that provides a unique glimpse of pristine artwork depicting archetypal shamanic journey themes dating back over 30,000 years. View the trailer.

Friday, July 29, 2011

"In the Light of Reverence"

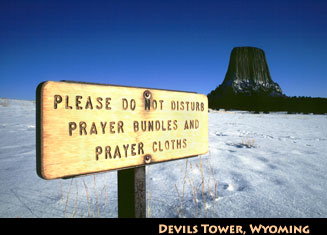

The award winning documentary, "In the Light of Reverence" explores three places considered sacred by American Indians: Devils Tower in Wyoming, the Colorado Plateau in the Southwest and Mount Shasta in California. The native peoples who traditionally care for these areas still struggle to co-exist with mainstream society. The film contrasts perspectives of Hopi, Wintu and Lakota elders on the spiritual meaning of place with views of non-Indians who have very different ideas about land, culture and what is sacred. The continuing degradation of sacred sites stems not only from colonial attitudes about the lands where native people live and worship, but also from prejudice and disrespect for native religions. Indian religious freedom is an environmental issue, and the destruction of sacred sites is the ultimate environmental racism. Watch the trailer or rent the DVD from Netflix.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Wild Sanctuary

Bernie Krause is an American musician, soundscape recorder and bio-acoustician, who coined the term biophony, which refers to the collective sound vocal non-human animals create in each given environment. Long devoted to sound and music, he has led an amazing life of exploration and innovation. From a classical musical background, to pioneering the use of the synthesizer in pop music and film, to his current explorations into the world of natural soundscapes, Krause continues to innovate new ways of perceiving and valuing the aural world. His company, Wild Sanctuary has produced over 50 environmental record albums and created environmental sound sculptures for museums and other public spaces. Google Earth uses Krause's sound layering technology to allow people to hear soundscapes from all over the world.

is an American musician, soundscape recorder and bio-acoustician, who coined the term biophony, which refers to the collective sound vocal non-human animals create in each given environment. Long devoted to sound and music, he has led an amazing life of exploration and innovation. From a classical musical background, to pioneering the use of the synthesizer in pop music and film, to his current explorations into the world of natural soundscapes, Krause continues to innovate new ways of perceiving and valuing the aural world. His company, Wild Sanctuary has produced over 50 environmental record albums and created environmental sound sculptures for museums and other public spaces. Google Earth uses Krause's sound layering technology to allow people to hear soundscapes from all over the world.

Krause's mission is to help connect people to the wild by presenting, preserving, and protecting the voice of the natural world, which is being lost due to increasing habitat degradation and human noise. Krause explains, "Natural orchestrations, the sounds of our unaltered temperate, tropical, arctic, desert and marine habitats, are becoming exceedingly rare and difficult to find. The keys to our musical past and the origins of complex intra-species connection may be learned from the acoustic output of these wonderful places. We are beginning to learn that the isolated voice of a song bird cannot give us very much useful information. It is the acoustical fabric into which that song is woven that offers up an elixir of formidable intelligence that enlightens us about ourselves, our past, and the very creatures we have longed to know so well."

Friday, July 15, 2011

Photographing the Essence of Healing

by Vance Gellert, PhD

"While the term smoke and mirrors is often pejorative when applied to some activity, suggesting something that is deceptive or fake, to me it is magic. Here it refers to the unexplained magic of healing that is part of the healer-patient relationship. As a pharmacologist I believe that in-depth studies of plants used for healing in indigenous cultures will provide the best source of finding new medicines. My strategy has been to not engage in documentary photography, but to interview healers and then observe and participate in their healing rituals. This portfolio is a story of my journey to healing knowledge that starts at the spirit of place and proceeding through the various facets of traditional and indigenous healing to how art and photography can lead to innovative ways of knowing." Read More

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Sami Musician Johan Sara

Johan Sara, the son of a reindeer herder, is one of the world's most famous Sami musicians. His CD, Transmission

is hypnotic and trance-inducing, reminiscent of the Sami shaman's joik. His is the sound of the icy wind blowing across the frozen tundra. It is the call of the wolf and the reindeer. The creative muse for this genre-free innovator is his people's archaic traditions and their Artic surroundings. Sara explains, "I learnt early in life the way of my people's joik. One's joik, is one's way. One's way of doing things, one's way of living and singing and making music." Read More

is hypnotic and trance-inducing, reminiscent of the Sami shaman's joik. His is the sound of the icy wind blowing across the frozen tundra. It is the call of the wolf and the reindeer. The creative muse for this genre-free innovator is his people's archaic traditions and their Artic surroundings. Sara explains, "I learnt early in life the way of my people's joik. One's joik, is one's way. One's way of doing things, one's way of living and singing and making music." Read More

Saturday, July 9, 2011

Breitenbush Hot Springs

|

| Breitenbush Steam Sauna |

For the past week, I have been camped near Breitenbush Hot Springs, adjacent to Mt. Jefferson, the great sacred mountain and second highest peak in Oregon. Since discovering the tranquil hot springs in 1980, I have made periodic pilgrimages to Breitenbush to "take the waters." I have visited sacred sites throughout North America, but Breitenbush is the most enchanting nirvana I have ever experienced.

Indigenous people worldwide believe that where fire and water mix at a hot spring is a sacred place. Healing ceremonies and like-minded gatherings have been traditionally held at these power spots. Hot springs are a link between the lower world and the middle earth plane and provide a means of tapping into those sacred feminine powers. A water deity, usually a goddess, resides in each spring. People make pilgrimages to thermal springs to connect with the goddess and to supplicate the benefits of her healing graces. The sacred ambience of the place, its geothermal energy and the pilgrim's relationship to it, is sufficient to fulfill the pilgrim’s aspirations.

I retreat to a remote streamside camp whenever visiting Breitenbush. A roaring white creek cascades steeply in a series of falls just feet from my idyllic encampment. It provides a unique soundscape in which to immerse myself for days at a time. The thunder of cascading water releases abundant negative ions, which open the portals of the mind to alternate realities. The water spirits resound day and night. I hear different qualities, depending on where I stand or sit. Sometimes it is a soothing wind like murmur and then a deep, reverberating boom. I can feel the waterfalls drumming my body like a great water drum. I float in a light trance much of the time.

I am truly inspired by the sacred ambience of this place. I hike, write or make music throughout the day as the mood hits me. I regale the spirits with song, flute, drum and rattle. I ask the water spirits to carry my musical offerings downstream to mother ocean, blessing all along the way.

I prefer to soak and commune at the hot springs early in the day when the veil between the physical and spiritual realms is at its thinnest. The rituals are simple and the prayers silent, out of respect for any pilgrims who may be taking the waters with me.

I begin my morning with a sweat in the rustic outdoor sauna. Rays of sunlight slant down through cracks in the roof and walls, illuminating the ethereal water vapors. The purifying steam cleanses my body, mind and spirit. As I suffer through the first of four rounds, one for each of the cardinal directions, the English lyrics to Jim Pepper's classic Comanche peyote song, "Witchi Tai To" begin to go through my head:

Water Spirit feelin' springin' round my head

Makes me feel glad that I'm not dead

The words lift my spirit and bolster me through each round of my thermal bath. Between rounds, I step out of the steamy sauna and cool off in a nearby claw foot tub full of icy cold water. After four cycles of fire and ice, I lounge outside the sauna, savoring the soothing whisper of nearby Breitenbush River. Feeling cleansed and renewed, I dry off and don my swim trunks and river sandals. I venture up the trail to the upper sacred hot springs.

As I enter the hot springs, I bend over and dip my hands into the pool and gently splash the healing waters across my shoulders three times, ritually cleansing myself. I offer silent prayers to the deity and spirit keepers of the healing waters. I pray for my own healing and the healing of all who enter the sacred pools. The heat from the mineral water sinks into my skin and muscles. My body sighs deeply. I gradually settle into a comfortable position and close my eyes. I hear water spirits singing in my head. It starts as a high pitch ringing, like a Tibetan bowl singing in my ear. I focus on the resonating tone and my ordinary world falls away.

In my reverie, I enter the watery depths of the dreamtime. My awareness follows the circuitous path of the springs deep into the earth back to their source. Like a sauna for the soul, the lower world’s intense heat and steam draw out any toxins, cleansing me completely. The inferno dissolves the existing order and fashions a new arrangement from the pieces. I am reborn in the fiery womb of the sacred mother. After a seemingly timeless sojourn, my awareness floats upward through her crust, bubbles into the pool, and then enters my dreaming body.

Satiated, I slowly arise, thanking the spirits for their water blessings. I step out of the thermal springs and the cool morning air tingles on my warm, moist skin. My body and spirit are aglow as I towel off and dress. I follow the path back to the lodge to share an organic meal with other rejuvenated pilgrims.

After enjoying the hospitality and vegetarian cuisine of Breitenbush Lodge, I return to my streamside camp where water ouzels flit about in the spray and dance along the mossy half-submerged boulders. These joyous song birds, who spend their lives feeding on the bottom of fast-moving rocky streams, are often my only companions in such remote aquatic places. I lie down for an afternoon siesta and a water ouzel alights in my dream; or is it the other way around? Am I the water ouzel dreaming of being a man?

Thursday, June 30, 2011

"The Calling"

Copyright © 2012

The spirits called me to a path of shamanism. I do not know why I was chosen. I ceased making such queries long ago. Over the years, I learned to just go with the flow. The how and why of my circumstances became less important to me than the lessons that I was learning along the way. As time passed, I began to see how my life experiences honed me into the artist I am today.

For as long as I can remember, I have been an explorer--pushing beyond familiar territory to investigate the unknown. As a child, I had a near-drowning, out-of-body experience that opened my eyes to the hidden dimensions of life and propelled my explorations. Like everyone, I was trying to find myself. I was also searching for something that resonated with me--anything that evoked a shared emotion or belief. I identified with people whose words were congruent with their actions. My inner self was most nourished when I was immersed in Nature. Being introverted and eccentric, I often felt a closer kinship to Nature than I did to people.

My birthplace was Oklahoma, but Topeka, Kansas became my home at the age of five until I moved away at age twenty-three. I was raised in a conservative Southern Baptist Church, which shaped my personal ethics and early life. I had my first ecstatic experience as a youth at a church revival, an evangelistic meeting intended to reawaken interest in religion. This state of rapture and trancelike elation inspired my spiritual quest. For much of my youth, I had aspirations of attending seminary to prepare for some form of ministry. I met my wife, Elisia, at a church function. We were wed by our pastor in a church wedding in 1976.

After I graduated from college in 1977, I felt a great pull to “Go West.” I mailed résumés to employers up and down the Pacific Coast. As fate would have it, I was offered a job with the Glidden Paint Company in Portland, Oregon. Elisia and I promptly sold our house and moved to Oregon. As a couple, that is how we often did things and that is how we still do things, after thirty-five years of marriage. We decide to do something, and then we just do it. Elisia and I have learned to trust and follow our inner yearnings. One of the things we learned working with spirits is that they often prompt us through urges to do one thing or another.

Upon our arrival in Portland Pacific Northwest . What I began to understand is that Nature sustains us and everything around us through an interdependent web of life. There is no separateness. We are all one consciousness.

In early 1980, I lost my retail managerial job. I was ready for a change and, with so much free time, I took up reading full-time. One of the influential books that I read was The Dharma Bums, a 1958 novel by Beat Generation author Jack Kerouac. Kerouac's semi-fictional accounts of hiking and hitchhiking through the West inspired me to embark, with my wife's blessing, on a backpacking/gold prospecting adventure to northern California

In May of 1980, my journey began with a bus ride to Yreka , California Sawyers Bar , California Etna Etna City Park

On day two, I arose early and continued my trek. After a few hours of steep climbing, I hitched another ride to Idlewild Campground, a forest service recreation area on the North Fork Salmon River six miles from Sawyers Bar , California

After a few days of unsuccessful gold-panning, I decided to backpack into nearby Marble Mountain Wilderness. I walked up Mule Bridge

I met no one along the trail. I was alone in the wilderness. Late in the afternoon, I came upon the skeletal remains of a large bear along the trail. It was one of the most peculiar sights I have ever beheld. The skeletal paws of the bear resembled human hands and the massive skull was quite intimidating. I later learned that a local bear hunter had reportedly shot a dangerous nuisance bear, but not had not killed it outright. The wounded bear had then escaped, but eventually died next to the trail.

I dropped my pack and walked a short distance down the trail to a river crossing. The North Fork Salmon River was swollen with spring snow melt, making it unsafe to cross. It began to drizzle again; it had been raining off and on all day. I had no choice but to turn around and look for a suitable place to camp for the night. Wouldn't you know it; the only level campsite was only a short distance from the bear skeleton.

I certainly was in bear country. There were tracks in the sand and mud all along the riverbank. I came across a bear footprint so large that I could step into it with my size 12 vibram-soled boots. It wasn’t a fresh track, but it was at the base of an ancient cedar in the very grove of trees where I was going to have to camp for the night. All of the large cedar trees in the area bore the claw marks of a bear marking its territory. The claw marks were so high on the tree trunks that I could barely touch them with my fingertips when standing on the tips of my toes. This was a very large bear and I was going to have to spend the night in its territory in a dark grove of trees along a raging river. I took some comfort in the fact that the tracks and markings might have been made by the bear that I discovered along the trail before it died.

I was nervous to say the least. I am always on my guard when trekking through bear country. After setting up my tent, I fired up my camp stove and cooked a hot meal. To minimize odors that might attract bears, I hung my nylon food bag from a high tree limb some distance away from the camp. I then gathered up as much firewood as I could find for the long night ahead. I found some cedar bark, which is good for getting a campfire started under soggy conditions. Once the fire was going, I stacked damp wood around the perimeter of the fire pit so that it would slowly dry. Heat from the flames warmed my face and hands and the warm glow perked up my spirits. As long as the fire burned, I felt relatively safe. I tended the flames late into the night until I finally ran out of wood.

Without the comfort of a warming fire, I had no choice but to crawl into my tent and try and get some sleep. I lay awake in my sleeping bag for a long time, listening to the night sounds. I focused intently on every strange noise I heard outside my tent. To get to sleep, I focused my attention on the current rushing over the river rocks. At times, the river made haunting sounds as it rolled big rocks along its course. At some point, I fell off into a deep sleep.

Then it started; the most terrifying experience of my life. I was awakened by a mysterious roar. It resembled the sound of a helicopter hovering directly over my tent. The previous day, before entering the wilderness, I had heard the "whop-whop-whop" sound of a dual-rotor logging helicopter in the distance. Helicopters, like all motorized vehicles, are prohibited in designated wilderness areas. Rationally, I knew it was highly unlikely that the sound was emanating from a helicopter hovering over my tent, yet a whirling windlike howl filled my ears in the predawn darkness. I have never been so frightened in all my life. I had spent countless nights camping in wilderness areas across the West and never had I experienced anything like this.

As I opened my eyes, I realized that I couldn't move, or I was too afraid to move. I was virtually paralyzed. I lay rigid inside my sleeping bag and prayed that whatever was outside my tent would just go away. My heart pounded like a drum. My panicked mind was reeling, as I struggled to classify what I was experiencing. Frenzied thoughts of UFOs, alien abductions, and even Sasquatch raced through my mind. I don't know how long the mind-bending experience lasted. It was all so surreal. I started to hyperventilate. Death seemed imminent.

Suddenly, the eerie moaning stopped and the bizarre incident ceased almost as abruptly as it had begun. I could hear the roaring river again, along with the pitter-patter of raindrops bouncing off the top of my nylon tent.

The paralysis ended immediately and I gasped in a lungful of air. I finally managed to sit up in my sleeping bag, my body trembling in shock. I sat motionless, lost in my thoughts, wondering what had just happened to me. The entire experience was much too real to have been a nightmare. As I relived the terrifying event in my mind again and again, the first light of dawn illuminated my tent.

I arose, hastily packed my gear, and then marched out of there as fast as I could. I retreated from the wilderness, returning to Idlewild Campground--back to familiar territory. Upon my arrival on May 18, (1980) I learned from a fellow camper that Mt. St. Helens 8:32 a.m. , killing fifty-seven people. The destructive power and devastation of the eruption served to distract me from my disturbing predawn experience. Though I prefer the isolation and quietude of the wilderness, I spent the remaining two weeks of my vacation camped in this developed campground, never venturing back into Marble Mountain Wilderness.

During my stay in this idyllic area, I made many new friends. I met mountain climbers, backpackers, gold prospectors, miners, kayakers, a hermit, and a colorful assortment of local hippies living on gold mining claims and growing weed. All in all, it was an epic adventure for me. I will never forget it. Idlewild Campground became a restful sanctuary for me at that moment in time. Where the North Fork Salmon River wrapped around my camp, the soothing sound of the water lulled me into a peaceful sleep every night.

Many years later I began to understand the significance of my anomalous Marble Mountain

I now also know that the

eerie howl that aroused me on that fateful night resembled that of a bullroarer.

A bullroarer is a thin, feather-shaped piece of wood that, when whirled in the air

by means of an attached string, makes a loud humming or roaring sound.

Bullroarers produce a range of infrasonics, extremely low frequency sound waves

that are picked up by the cochlea (labyrinth) of the ear, stimulating a wide

array of euphoric trance states. The bullroarer dates back to the Stone Age, and

is probably the most widespread among all sacred instruments. With over sixty

names, it is universally linked to thunder and spirit beings in the sky.

The first time I actually

heard a bullroarer was in December of 1991. Elisia and I were traveling through

New Mexico

On the day of the Shalako ceremony, the six kachinas, one for each of the four cardinal directions plus zenith and nadir, entered Zuni Pueblo at dusk. Each Shalako deity was escorted by a group of singers and an attendant whirling a bullroarer over his head. As the first procession filed into the plaza, the sound of the bullroarer elicited an intense feeling of déjà vu, triggering memories of my traumatic experience in Marble Mountain Wilderness. Reflecting on my ordeal created anew the conditions for revelation, learning, and reintegration. I finally realized what had transpired on that life-altering night in 1980. Although I didn’t know it back then, my guardian or tutelary spirit was "calling" me. Chosen by the spirit of a bear, my shamanic initiation had begun and, like a sluggish bear emerging from the slumber of winter hibernation, I gradually awakened to the knowing of my true self.

I have since had other initiation experiences, such as a shamanic death-and-rebirth. However, none of these subsequent experiences have impacted me as much as my

That mystical encounter with

Spirit shattered my ego, cracking me wide open. Shamanic initiation serves as a transformer--it causes a radical change in the initiate forever. It is

typically the final step in becoming a shamanic healer, a process that is facilitated

by the aspirant’s shamanic teachers as part of a training program. However,

initiation may also be spontaneous, set in motion by Spirit’s intervention into

the initiate’s life. It is probably the most powerful and least understood of

all forms of spiritual awakening.

This excerpt also appeared in the 2015 book "Shamanic Transformations: True Stories of the Moment ofAwakening." It is a collection of inspiring accounts from contemporary shamans about their first moments of spiritual epiphany. Contributing writers include Sandra Ingerman, Hank Wesselman, John Perkins, Alberto Villoldo, Lewis Mehl-Madrona, Tom Cowan, Linda Star Wolf, and others.

This excerpt also appeared in the 2015 book "Shamanic Transformations: True Stories of the Moment ofAwakening." It is a collection of inspiring accounts from contemporary shamans about their first moments of spiritual epiphany. Contributing writers include Sandra Ingerman, Hank Wesselman, John Perkins, Alberto Villoldo, Lewis Mehl-Madrona, Tom Cowan, Linda Star Wolf, and others.

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Free Shamanic Songs Download

A collection of 14 multicultural and original songs and chants sung by Michael Drake. Singing and drumming are extremely powerful tools for restoring the vibrational integrity of body, mind, and spirit. When coupled together, they move us to a level of awareness beyond form, a place where we discover our own divinity. Each song and chant on this recording has a specific purpose for invoking or paying homage to spirit beings and deities. Each one creates a vibratory resonance that allows these forces to be called forth. Tracks: Introduction, Eagle Chant, Hummingbird Chant, Coyote Chant, Bear Chant, Buffalo Chant, Horse Chant, Earth Chant, Rainbow Fire Chant, Raven Song, Forest Song, Cherokee Morning Song, Wolf Chant, Song to the West, Sedna Song. Download Sacred Songs & Chants at Archive.org. See more of our Free Downloads

Friday, June 24, 2011

"The Last of the Shor Shamans"

The Last of the Shor Shamans focuses on the fundamentals of Shor shamanism from interviews with the few remaining authentic shamans from the

focuses on the fundamentals of Shor shamanism from interviews with the few remaining authentic shamans from the Shor Mountain Siberia . The authors Alexander Arbachakov and Luba Arbachakov are themselves indigenous Shors, which only substantiates their study even more. The book provides details surrounding shamanic practice, spirit communication, and shamanic drumming. It examines how the shamanic drum is constructed, how it is played, and the role it plays in shamanic ceremony. In short, the reader gains insight into the meanings behind every component of the drum and performance methodologies. This much needed book may be the only way the vanishing indigenous Shor people are remembered. It is a prized work for scholars in Siberian shamanism, folklore, and cultural studies.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Can Archetypes Be Heard?

Copyright © 2011 by Gianfranco Salvatore

When we hear a melody, a rhythm or a mere sound, we sometimes feel an emotion that goes beyond mere sensory perception, but is not necessarily limited to an aesthetic emotion. A touch of the arcane together with a certain feeling of uneasiness can help us define this sensation as a 'primordial' emotion. At these moments, one is projected into the world of the symbolic by means of sound and music.

This is not an instance of 'phonosymbolic' sound, whereby the music stands for a realistic or emotional situation. lt’s not an instrumental sound or a musical phrase alluding to a concrete presence or to a natural phenomenon, by means of the imitation of sounds in nature. Neither is it an example of Affektenlehre - intending or attempting to reproduce through music certain ‘emotional curves’ in human feelings.

I would like to discuss the symbolic power of music (as well as the modes of perception of a certain kind of sound symbolism) from a wider perspective than that which is offered at present in the field of musical studies. Archetypology, the definition and classification of archetypes has, until now, dealt with conceptual and visual data that occupy primordial positions in human imagery. The aim of my research is to extend its theses to the field of sound, in order to formulate an archetypology of music.

According to some scholars, the study of archetypes goes as far back as Plato’s doctrine of 'ideas', or even as far as the PreSocratics, but in modern culture the first systematic definition of archetypes took place in Jung's work, and in particular within his theory of the collective unconscious. Charles Kerényi later discussed archetypes in more phenomenological terms related to the study of religious thought. But only with Gilbert Durand has archetypology been given its own anthropological context, within the study of the Symbolic: Durand pointed out the possibilities of the perception of archetypes, based on data of a non-sensory nature.

I would like to try to apply certain fundamental elements of Durand's theory to music, in particular to its perception and emotional power, but I will use them from a different angle even methodologically, making use of a more simplified formulation. One could begin by asking why music is usually ignored in the study of symbolic thought. This branch of study has inexplicably imposed limits upon itself by exploring the aesthetic domain almost exclusively in its literary and figurative contexts. Even the more modern studies in the history of religion tend to select mythologies and rituals, narrative functions, and concrete, visible symbols. The whole realm of the 'audible' is normally excluded in the analysis of symbolism. The symbolic figures are also usually considered in their static and bi-dimensional form, and this constitutes a restriction typical of the late European cultural sensibility. For instance, we are used to conceiving as a flat image the symbol of the cross, which Early Christians could still see as a symbolic representation of six directions within space, according to a tradition that goes back to the Hebraic doctrines. Only Oriental symbology, that draws the cross as a swastika, still recognizes in it the sense of a vector, in this case a clockwise rotation. Dynamic conception of the symbol is common to many other Oriental symbols, such as the cosmic wheel. And Oriental symbology recognizes chant and music as having symbolic status, and considers sound as being at the origins of the cosmos, conceiving the universe as vibration, singing the sacred syllable AUM with complete awareness of the symbolic meaning of each of its sound components.

Before Gilbert Durand's work, studies of the Symbolic neglected the dynamic and cinematic aspects of symbols. Durand started to consider archetypes not as images but as deep figural impulses that determine the creation of symbolic motifs and images, thus providing the symbols with their original matrices and dynamic roots. But Durand's analyses, despite this widened perspective, end up concentrating again on the archetypal visual images and their structures, leaving music outside the argument. One must remember that music is not just an art of time, but also possesses an apparatus of concepts and metaphors of its own, in order to indicate imaginary positions in space (i.e., high and low pitches). Music treats sound as an element in motion, with its own directions, and thus it takes on a cinematic and vectorial meaning. Moreover, the contributions of music to symbolic imagery should also include the means by and the conditions in which it is produced (in that which can be defined as the ‘musical act’), so that the power of music in its functioning as a 'sound gesture' enriches itself by the actual gesture with which the performer provokes the vibration of the sound instrument.

Taking this argument to its extreme limit one can discover that music also, just like any other image of movement, has the power to reproduce archetypal motifs by means of a dynamic-cinematic symbology that is often analogous to the visual productions of symbolic images. Furthermore, within the sounds actually emitted lies a symbol reflective of the dynamic patterns from which they are produced. It can be demonstrated, in fact, that in determined ritual contexts the acoustic element and its traditional ways of production express, with sounds and gestures, the same archetypal patterns as the visual elements of the ritual.

An approach toward archetypological-musical analysis can begin with a very simple sound instrument used in the most archaic rituals, possessing a ceremonial function. Thus it will be possible to examine its technique in the production of sound and compare it with the symbolic structures within the rituals in which the instrument is used.

The bullroarer was used as far back as the Stone Age. Present within the archaic civilizations of all five continents, it is probably the most widespread among all sacred instruments, and in ancient Greece it was sacred to Dionysus. In pastoral civilizations the sound of the instrument is considered to be the voice of a god, and the divinity evoked by the bullroarer is generally a Bull God (as Dionysus was for the Greeks). In a context of natural magic, the voice of the Bull God (the sound of the bullroarer) is identified with the roar of thunder.

The structure of the bullroarer is very simple: it is made of a throad a few meters long, to which is attached a wooden or bone elongated object, usually spindle-shaped. André Schaeffner emphasized the fact that the bullroarer's shape alludes to that of a fish; its symbology, in fact, is associated with water. Often used to invoke rain, according to a principle of homeopathic magic, the bullroarer imitates the sound of thunder; where there's thunder, there will be water. It's not just by chance that in ancient Greece, the bullroarer was sacred to Dionysus, a god of the ‘liquid’ element.

What is the relation between the sound of the instrument, its techniques, and its archetypal meaning? The sound of the bullroarer is produced by the rotating of its thread, which traces in the air a circular trajectory, whose axis is the performer's arm (he provides the impetus by turning his wrist, but holding his arm still). Al the same time, the spindle revolves around its own axis. But the circles traced in the air by the components of the bullroarer are never quite the same, so that the thread and the spindle describe, in fact, two spirals, or two vortices. The bullroarer's movement is therefore double, and its sound is composed of two sounds. Basically, the thread gives off a high-pitched sound, just like that of a fine whip, but a continuous one; whereas the spindle, shorter and thicker than the thread, generates a low-pitched sound, similar to a deep drone. Interference between the two spiral-shaped movements also produces interference between the two sounds. Since the impetus of the performers arm is constant but never regular, the frequency (and therefore the pitch) of the sound oscillates, producing the howling quality of the bullroarer's sound that made it comparable to the roar of thunder and to the bellowing of the bull.

The meaning of the bullroarer's sounds is utterly analogous to certain conceptual and 'visual' meanings of the archetypes to which it is related. In order to show this analogy, various symbolic elements must be organized into a sequence that can be defined as a mythical-ritual scenery. The two symbolic connotations mentioned above - the roaring of thunder (with its symbolic association to water), and the bellowing of the bull (that represented the sound epiphany of Dionysus) are not as heterogeneous as they may seem. The Bull God cult was in fact common to all Neolithic civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean. Dionysus only represents a late and even 'classical' aspect of this archaic cult. But originally, the sacred bulls' and cows' horns were considered images of the Moon. The moon is one of the most important archetypes, because it cyclically influences any occurrence related to the liquid element: tides, menstrual fluxes, the regenerating of lymphs in plants and thus of nature as a whole. Therefore on the human level, as well as on the animal and vegetable, the moon regulates fertility and fecundity, in other words, the cyclical regeneration of life. But the roaring thunder that announces the coming of powerful waters is just one aspect of the symbolism related to the roaring of the 'lunar' bull. Also commonly associated with the bull-related symbols of antiquity was a major cosmic archetypal image: the spiral.

A bullroarer produces its sound on the basis of a double spiral shaped movement: is this incidental? No. This sound, in fact, tends towards that of the great cosmic spiral, that the universal cosmogonies associate with the creation of the world as it is now (meaning after the end of the mythical Age of Gold), for which the Bull God is the demiurge, or at least a tutor. Symbolically, the visual aspect of the ritual rotation of the bullroarer thus perfectly corresponds to its sound aspect. Such a statement would not be possible outside the dynamic-cinematic conception of symbolic production: in other words, outside archetypology.

The archetypal nature of the spiral-shaped movement and of the sounds that are related to it is verifiable in various other cases. During the Athenian Anthesteria festival, spiral shaped honey sweets used to be offered in the cult of the dead; and Dionysus, in Greek religious imagery, is in fact the 'dying god'. As a baby, he was killed by the Titans, who distracted him by giving him toys. Among these toys was a bullroarer (as discussed above, a generator of visual and sounding spirals). There was also a top, a cone which, by spinning on its tip, traces eccentric spirals on the ground. Not one scholar of Dionysism has realized, despite the number of archaic civilizations whose rituals used sacred tops, that the top is an aerophone: its cone is a hollow resonator, with holes which let the air within vibrate. Thus, the top's movement, as well as its sound, are comparable to those of the bullroarers spindle.

Further certification is given by the homology of sound and visual symbols within the dynamic schemas of sacred dances. One of the most often recurring movements in the ecstatic dances of Dionysus' priestesses, the Maenads, was a spinning motion, another symbol connected to the archetypal spiral, comparable to the sound of the bullroarer that used to announce, to the Maenads, the epiphany of their god. The similarity between this spinning motion and the Dervishes’ dances confirm to us that this meaning is not only cosmological, but also initiatory: in other words, the ritual dance aims establishing the identification of the believer with his god through a psycho-motory technique of trance. The rondes, or circular dances, that took place collectively around a centre of a sacred axis, real or imaginary, had an analogous meaning. This circular movement schema is the matrix of the spiral-like motion that was developed within the sacred labyrinthine dances. Various scholars, from Charles Kérenyi to Giorgio Colli, have demonstrated that the Minotaur, at the centre of the Labyrinth in the myth that took place in Crete, is an archaic form of Dionysus. The defeat of the Minotaur (meaning the initiatory identification with the Bull God) was celebrated with a labyrinthine dance, which, according to the myth, was accompanied by the seven-stringed Apollonian lyra. Seven is the number of circular paths within the Labyrinth, and the number of planets in archaic astronomy, as well as the number of levels that separate one world from the other. The journey/dance within the Labyrinth was thus accompanied by a music whose scale criteria were analogous to those that ruled the ‘harmony of the spheres’ in the Pythagorean doctrines.

The Labyrinth was also associated with another instrument, the shell trumpet. This wasn't used in the labyrinthine dances, but nevertheless some ancient lexicographers defined the Labyrinth as a “shell-shaped place", and the poet Theodoridas called the conch a “sea labyrinth”. It is a known fact that conical conch-shells were blown as horns. In the writings of the poet Ovid this marine instrument was associated with Triton, who plays it in order to call back the waters of the flood. Homeopathic symbolism is evident there: the conch shell (daughter of the sea, which pressed against the ear produces the sea’s sound) is played in order to recall the sea itself; the similar attracts the similar. And not by chance, among various civilizations, the shell trumpet has the ritual function of attracting rain, just like the bullroarer. Thus, even its archetypal dominion is that of the moon that attracts the fluxes: in India and in Mexico it is considered an attribute of the lunar gods. In other words, the shell-trumpet has the cyclical meaning of a death/rebirth process: the same archetypal meaning of the Labyrinth, which constitutes a biological equivalent to it.

The helicoidal development of the conch shells, in fact, represents a case of the logarithmic spiral, studied by structural biology, a schema to which the bull's horns belong. And so the sound of the shell-trumpet may be considered another of the Cosmic Spiral’s sound emanations, which here takes on the symbolic value of the 'sound of the abyss', just as the bullroarer in the Dionysiac rituals has the ritual function of the 'sound of trance'. In any case, it’s a sonority to which is attributed the power of attracting, because the instruments that produce it reflect (within their structure, or more often within their movement) the archetypal shape of the Spiral.

A study included in my book Sounding Islands (Isole Sonanti, 1989) led me to conclude that the shell-trumpet was a cult instrument sacred to Aphrodite or more accurately, to the Mediterranean pre-Olympic divinity, a Great Goddess associated with water and with the moon, who then became Aphrodite. The classical iconography has attributed to Aphrodite the bivalvular shell from which, according to one myth, the goddess was born, but a famous Minoic gem has a Cretan Aphrodite's priestess engraved upon it, who plays the shell-trumpet before the altar in order to summon the goddess, invoking her epiphany. The function of the instrument is therefore analogous to that of the bullroarer within the Dionysiac rituals. And Dionysus and Aphrodite are in fact connected by two important factors: both represent the power of the liquid element, and both were originally hermaphrodite divinities, as various cults certified in the Greek world. This is the androgyny of the primordial divinities who express the undifferentiated nature of the primary substance. Another primordial divine function, that of being in charge of cyclical movements and transformations, was represented by circular symbols such as the Uroboros (the snake eating its tail) and the Cosmic Spiral. Spiral-shaped shells are produced by hermaphrodite mollusks; objects which designate a symbol are never arbitrary. And this is true for sound instruments as well.

The sound of the shell-trumpet stands for the sound of the sea, of water, and of the undifferentiated element that generates the cyclical movement, and through this the power to attract. When the Olympian Aphrodite emphasized her function as Goddess of Love more than her other archaic powers, a new sound instrument was consecrated to her: the iynx. Considered as an amulet for erotic magic, even the iynx manifested an expression of the power to attract: making the beloved come near to the lover. The scholar A.F.S. Gow described the iynx as "a spoked wheel (sometimes it might be a disc) with two holes on either side of the centre. A cord is passed through one hole and back through the other. If the loop on one side of the instrument is held in one hand, and the tension alternately increased and relaxed, the twisting and untwisting of the cords will cause the instrument to revolve rapidly, first in one direction and then in the other". The sound produced by the iynx is a kind of humming hiss, analogous to that of the bullroarers thread (as the sound of the sounding top is analogous to that of the bullroarers spindle.)

Here we find yet another meaningful coincidence, where the analogies of movement are intermediaries between the analogies of symbolic functions. Even the movement of the iynx's wheel is in fact a spiral-like motion. Turning backwards and forwards alternately, the iynx’s wheel describes a double spiral; or even better, two spirals standing on the same axis (the iynx’s cord) and with a common vertex, cyclically alternating their sense of rotation. We are still in the presence of a sound epiphany of the Cosmic Spiral that, with the bull-roarer and the iynx, expresses two different forms of attracting. Perhaps this is why the iynx and the bullroarer were often confused by Greek and Latin classical authors. But, if the sounding top is in fact a dynamic image of a cosmogonic myth, the combined movement of the bullroarers thread and spindle synthesizes the top's movement and that of the iynx, thus fusing a cosmic image with an erotic calm. The ritual function of the bullroarer is to invoke the fertilizing (or 'erotic') role of a cosmic power such as the Bull-God, or to evoke the thunder that, with the rain, will bring fecundity and the renewal of the biological cycle. This synthesis of ritual function perfectly corresponds to the interference between two sounds: that of the top and that of the iynx, respectively equivalent (in their archetypal meaning as in their sonority) to the bullroarer’s thread and spindle.

There was perhaps a time when the power of sound, almost like a code of dynamic forms and gestures, expressed symbolic meanings exactly in the same way as visual images do for us today. A forgotten language of which only a mere fossil remains in our spirits: the slight uneasiness that creeps up on you when you hear those archetypal sounds.

Gianfranco Salvatore has studied sonic archetypes for many years. A composer who deals primarily with the interaction between experimental pop and serious music, he has also produced several recordings, and writes as a music critic for several publications in Italy. As a musicologist, his research mainly concerns the language of improvised music - ethnic, jazz and contemporary. He considers improvisation as performances with anthropological meaning, actions during which the improviser, by means of improvised patterns and spontaneous inspiration, realizes and shapes his culture within the circumstances of the environment. The author of three books and several audio-dramas (based on the mixing of musical and verbal signals) he is currently preparing a new book entitled Cerchio, Spirale, Vortice (Circle, Spiral, Vortex), concerning the archetypal meaning of circular shapes and motions both in visual and acoustic symbolism.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)