Sunday, May 28, 2023

The Drum Makers of Cochiti Pueblo

Sunday, April 23, 2023

The Pueblo Moccasin Makers

Sunday, April 9, 2023

Pass the Pipe

Sunday, March 26, 2023

Court Case Threatens Native Sovereignty

Sunday, March 12, 2023

FNX - First Nations Experience

At the ceremonial unity launch of FNX in February 2011, Cherokee actor Wes Studi confessed he didn't see this coming. "Thank you for proving me wrong," Studi said, speaking at the KVCR/FNX studios in San Bernardino, California. "I once said that I didn't think in my lifetime I'd see a TV channel dedicated to Indian people like you and me, people who are rarely seen on screen in authentic ways. We're making history with this powerful new media tool. This is something I can tell my grandchildren about -- I'll tell them I was there when it launched."

San Manuel Tribal Chairman James Ramos said FNX is "fulfilling a dream our ancestors had ... using the resources we have built through gaming. It's important that people know what our ancestors had to go through so we could be here today. It's time for us to change negative perceptions about indigenous peoples in mainstream audiences. We need to stand together as one voice and make things better for our people."

Ramos added context from his own tribe's past. "There was a time in California's history when there was an effort to get rid of Indian people; we were shot and killed here in the San Bernardino Mountains," Ramos said. "Many people never heard that story, and today some people don't want to talk about that history. But it's important that we do so that we can learn from the past and move forward working together for a better future."

Sunday, March 5, 2023

Remembering Indigenous Rights Advocate James Abourezk

Sunday, February 26, 2023

Imaginary Shamans

Sunday, February 19, 2023

The Shaman's Rattle Beater

Sunday, January 22, 2023

Music Born of the Cold

Sunday, January 8, 2023

However Wide the Sky: Places of Power

Pierce worked with tribal leaders to film on the land. The areas chosen are: Chaco Canyon, Bears Ears, Zuni Salt Lake, Mount Taylor, Pueblo of Santa Ana, Taos Blue Lake, Mesa Prieta and Santa Fe. These places intimately connect the people and their beliefs to the natural world. This is their story, of the land and who they are. Pierce says the concerns about the use, misuse, development, drilling and mining of scared places in New Mexico began a conversation between Silver Bullet Productions and tribal leaders about the importance of education in 2016.

Sunday, November 27, 2022

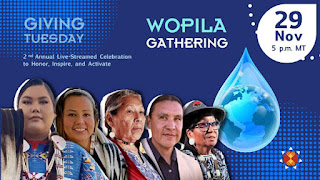

Second Annual Wopila Gathering

So I hope to see you there! And please extend this invite to those you love by clicking the social share icons -- to Facebook, Twitter, and email -- on our Wopila Page. Let's continue to grow the circle of support and come together to honor, inspire, and activate! Stay tuned for more info soon.

Co-Director and Lead Counsel

The Lakota People’s Law Project

Sunday, November 13, 2022

Manchu Shamanic Drumming

Sunday, October 16, 2022

Meeting Author William S. Lyon

Sunday, September 18, 2022

Dark Ecology

Sunday, September 11, 2022

World Tree Meditation

Sunday, September 4, 2022

The Origin of Disease and Medicine

Sunday, July 17, 2022

Words Are Monuments

• 10 racial slurs

• 52 places named for settlers who committed acts of violence against Indigenous peoples. For example, Mt. Doane, in Yellowstone, and Harney River, in the Everglades, commemorate individuals who led massacres of Indigenous peoples, including women and children.

• 107 natural features that retained traditional Indigenous names, compared with 205 names given by settlers that replaced traditional names found on record.

While the Department of the Interior has established a task force to address derogatory place-names, the agency has faced some criticism for what Washington State officials and area tribes are calling a rushed process, with proposed replacement names that are largely colonial.

• Why place names matter and how the movement to 'undo the colonial map' relates to other movements that reckon with American history -- to topple Confederate and colonial monuments, decolonize museums, and overhaul school curricula;

• The relationship between language and ideology, and the power of place names in encoding a way of seeing, understanding, and relating to the land;

• How campaigns to re-Indigenize place names on federal lands are not just about making public lands more inclusive, but are stepping stones on the path to Indigenous co-governance and land rematriation;

• The global reckoning with colonial and imperialist history, including successful and ongoing efforts to replace colonial place-names in New Zealand, India, Palestine, South Africa, and beyond.

Sunday, June 19, 2022

Chief Arvol Looking Horse Calls for Unity

Chief Arvol Looking Horse

19th Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe

Sunday, June 5, 2022

The Lost Art of Resurrection

Sunday, May 29, 2022

"The Shamanic Bones of Zen"

Manuel speaks in deeply personal rather than theoretical terms about the underlying shamanic reality of Zen practice. Such awareness is crucial for the development of contemporary Western Zen. Displaying reverence for the Zen tradition, creativity in expressing her own intuitive seeing, and profound gratitude for the guidance of spirit, Manuel models the path of a seeker unafraid to plumb the depths of her ancestry and face the totality of the present. The book conveys guidance for readers interested in Zen practice including ritual, preparing sanctuaries, engaging in chanting practices, and deepening embodiment with ceremony. The Shamanic Bones of Zen will turn your conception of Zen inside out.